Helmetshrikes: characters of the bushveld

The helmetshrikes comprise one of the most distinctive groups of birds that you find in the Hoedspruit area where I live, and throughout the South African bushveld. They are never far away, and family groups are often seen on their own or as part of a bird party as they forage among the trees and bushes. We have two species in our area, the white-crested helmetshrike, Prionops plumatus and the Retz’s helmetshrike, Prionops retzii. As I write this, a family group of Retz’s helmetshrike is foraging in the trees outside my home-office, making their characteristic grating ‘tweeooh-tweew’ calls.

The helmet shrikes belong to the family Vangidae, which is a family of shrike-like birds that is distributed from Africa to Asia and that includes the vangas of Madagascar from which the family gets its name. Like our two species, the typical helmetshrike species all belong to the genus Prionops, which is endemic to Africa and includes some species that are local endemics. For example, the Gabela helmetshrike, Prionops gabela, is endemic to Angola and the yellow-crested helmetshrike, Prionops alberti, only occurs in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In addition to the two local species mentioned above, there is a third species that occurs in southern Africa, also belonging to the genus Prionops, the chestnut-fronted helmetshrike, Prionops scopifrons that is found in Mozambique and up the east African region to Somalia.

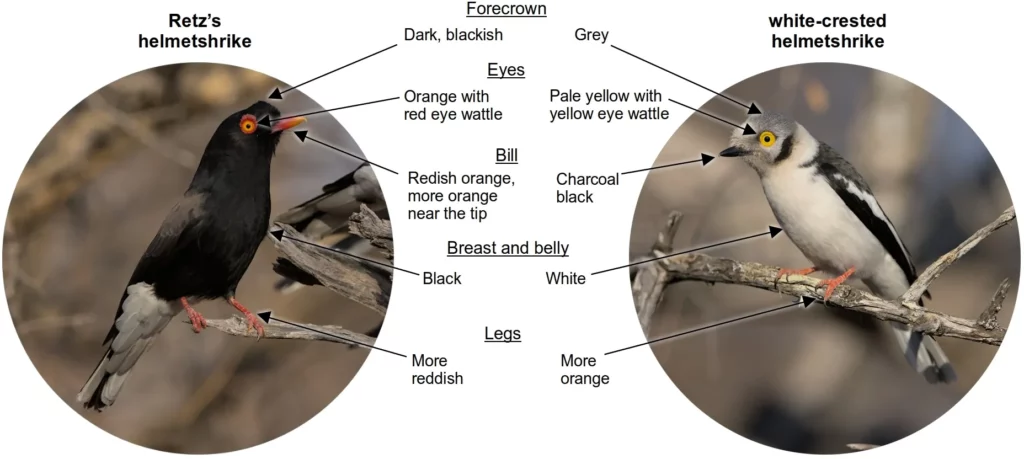

Although they behave similarly, our two species are strikingly different in appearance so easy to tell apart. White-crested helmetshrikes are essentially black and white birds with prominent yellow eye rings, a grey forecrown and a black bill. Retz’s helmetshrike are overall blackish birds with a prominent red eye-ring surrounding an orange eye, and a distinctive red and orange bill. For both species, the sexes are alike in appearance.

Helmet shrikes were once placed in the family Laniidae, the true shrikes. Other suggested relationships have included the bushshrikes, family Malaconotidae, or the cuckooshrikes, family Campephagidae. However, subsequent work, including genetic analysis places them firmly within the Vangidae. The evolutionary history of this group is still a bit confused, and if you look at ONEZOOM (http://www.onezoom.org/) you will see that the evolutionary tree presented makes little sense. There is still plenty of work to be done. However the genus Prionops probably arose around 17 million years ago during the Neogene period, with the split between Retz’s and white-crested occurring potentially around 5 million years ago.

They occur in deciduous, broad-leaved woodland, and Vachellia savanna with the white-crested helmetshrike having a somewhat broader distribution in South Africa than Retz’s. Both species are active birds, and their strongly vocal and sociable nature suggest a lot of character. This makes them excellent candidates for behaviour watching, especially during the breeding season and the feeding of fledglings. Both typically move around and hunt in noisy family groups, with a tendency to feed more in trees in the summer wet season, and on the ground during the winter dry season.

Despite their obvious visible differences, the fact that they overlap considerably in distribution, habitat, food, and behaviour makes one wonder how they manage to co-exist. They are often seen foraging together, and during the past summer I often had both species feeding young at the same time in the trees behind my house. It has been reported, and it seems to often to be the case around Hoedspruit, that Retz’s helmet shrike tends to feed higher up in the trees than white-crested helmet shrikes, and rarely descends to the ground even in winter.

Family groups for both species tend to be a similar size, typically 2-10 individuals but expanding to 20 or more individuals outside the breeding season. They feed on insects, spiders and small lizards, the latter more common for the white-crested helmet shrike.

Both local helmentshrike species are cooperative breeders and nest building is shared among members of the group as they build a shallow rounded cup shaped nest that is bound together with spider webs and well hidden up in a tree. There are indications that the Retz’s helmet shrike nests tend to be higher up in the trees. They lay 2–5 eggs, and incubation is typically shared among all members in the group including the juveniles, and lasts for around 20 days. All members of the group also take turns to feed nestlings.

Helmetshrike pairs are monogamous unless a mate dies. The family groups have some dominance hierarchy within them, and it is headed by the breeding female for both species. Females are higher in the dominance hierarchy than males of the same level. According to Robert’s Birds, the dominance hierarchy for white-crested helmetshrikes is as follows: breeding female > breeding male > other adult females (usually siblings of the dominant, breeding female) > other adult males (usually siblings of the breeding male) > 1-year old birds > younger juveniles. A similar hiearchy is also shown by Retz’s helmetshrikes.

The dominant pair may sometimes be seen allopreening, that is grooming one another, which is involved in maintaining pair bonding. Data from over 500 species of birds show that allopreening between breeding partners is more common among species where parents cooperate to rear offspring. Allopreening may have evolved in species where reproductive success is strongly dependent on strong pair bonds between breeding partners. If you spend some time watching a family group of either species of helmetshrike you stand a good chance of observing this behaviour.

Rainfall probably has a strong influence on breeding success in both species. We know from studies in Zimbabwe that rainfall during both the previous breeding season and current breeding season influences the number of nests and clutch sizes for white-crested helmetshrikes. I have not seen any published information on rainfall effects on Retz’s helmetshrike, so this may be something worth further study.

Retz’s helmentshrikes are the only known host to the brood parasite, thick billed cuckoo in our area. Following Retz’s helmentshrikes during the breeding season might be a good way to find thick-billed cuckoos. I managed to do this last year at Balule in Kruger National Park, and found the cuckoo, but did not manage to get a photo. Maybe this summer I will be successful.