I love ruffs. Part of the reason for this is that they arrive in Gauteng, South Africa from the northern hemisphere during the chill, dusty winds of August and provide the first sign that our winter is almost over. It is especially nice to see them soon after arrival, when some of the few males that we get still bear the scruffy remnants of their breeding plumage. I always hop out to the Marievale wetlands in August to see if the ruffs have arrived yet.

What are ruffs?

The ruff (Calidris pugnax) belongs to the sandpiper family, the Scolopacidae, within which the genus Calidris contains 23 other species. Other common visitors to South Africa in this genus include the little stint (Calidris minuta) and the Curlew sandpiper (Calidris ferruginea). The species name refers to the aggressive behaviour of the bird during the mating season, pugnax being derived from the Latin term for “combative”.

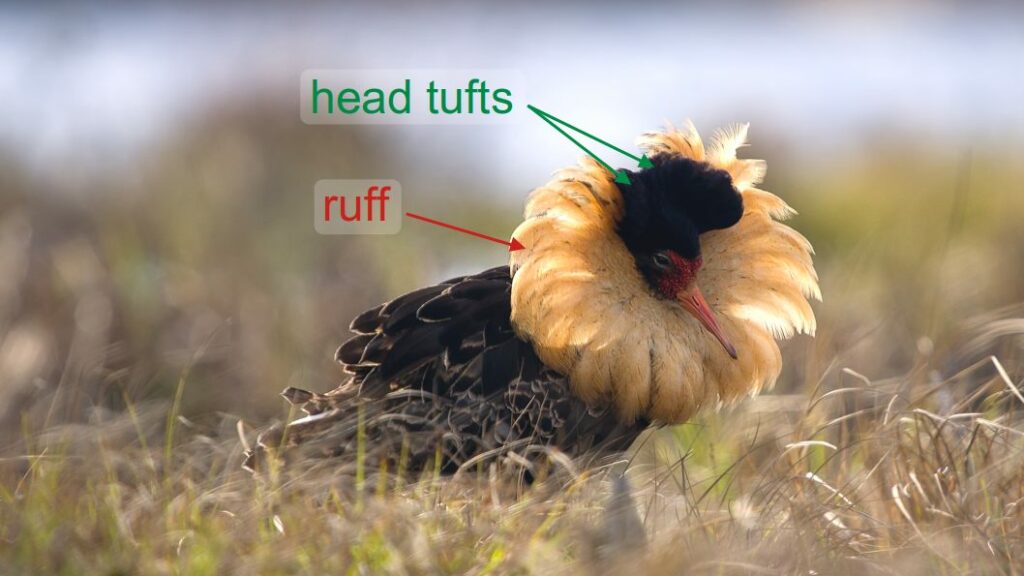

Outside the breeding season, they are ordinary, plump-looking sandpipers. In the breeding season, however, some of the males develop a range of different nuptial plumages that involve ornamentation of the head and neck.

Ruffs forage mainly in wet grassland and soft mud, probing with their bills or searching by sight for edible prey. They feed mainly on insects in the breeding season, but are not above eating rice and maize in cultivated fields, as well as other seeds, when undergoing migration.

Their summer breeding grounds comprise marshes and wet meadows across northern Europe and Asia, and they overwinter in southern and western Europe, Africa, southern Asia and Australia. Ruffs are highly gregarious during migration, travelling in large flocks that can contain hundreds or thousands of individuals. Huge dense groups form on the over-wintering grounds, with one flock in Senegal having a million birds. We don’t get numbers like that in southern Africa, but they still aggregate in smaller numbers even at Marievale.

The non-binary nature of ruff gender

We often talk of gender based on different expressions of a biological sex. In this context, ruffs can be considered to have five genders based around two sexes:

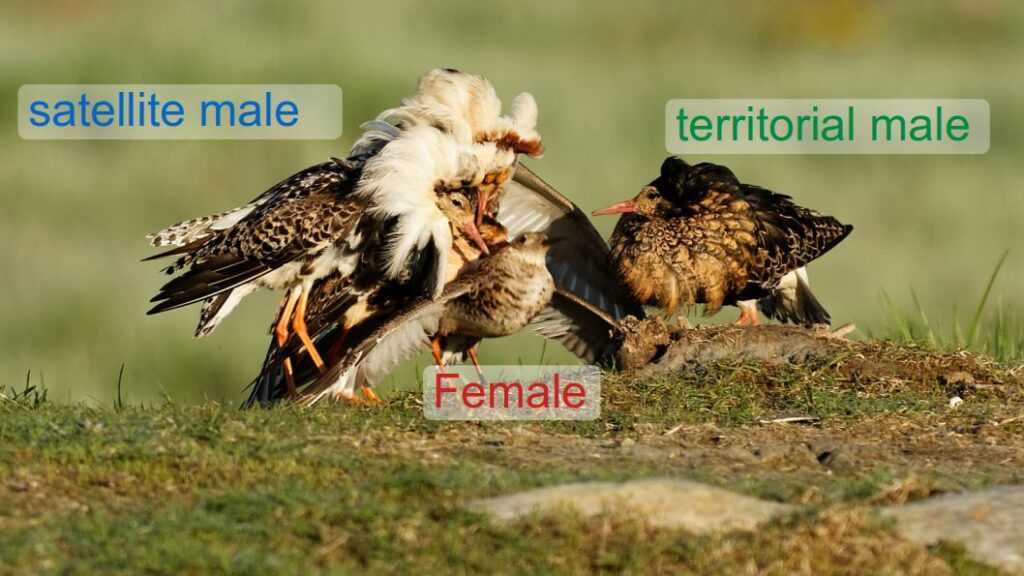

- Independent (territorial) males

- Satellite (non-territorial) males

- Female mimics (faeders, sneaky males)

- Breeding females

- Female faeders

Independent or territorial males are typically decorated with a nuptial display plumage of ruff (around the neck) and two feather tufts (on the head) during the breeding season, and they obtain and hold territories (see later). Satellite males are also similarly decorated, but do not seek or hold territories. Female mimics completely lack ornamental breeding plumage during the breeding season, instead closely resembling females. Females are a smaller than territorial and satellite males, and more drab in plumage. In 2013, a fifth form was discovered, called female faeders, which are a smaller female morph about which not much is known.

The lek

Ruffs make use of leks for breeding. To understand how these genders operate in the ruff breeding system, we need to first understand the lek.

A lek an aggregation of maleswhich gather to carry out competitive displays and courtship rituals together in a common location to entice females to the area for mating. The males of lekking species are often strongly ornamented, and put on strong displays to entice females to mate with them. Such species are typically characterised by strong female choice in the mating process, which leads to strong sexual selection for male behaviours, vocalisations, and ornamentation.

During the breeding season, territorial males and satellite males gain their impressive breeding plumage, with the thick collar of feathers that resembles a ruff – circular frill or ruffle at the neck that was popular in 1560s–1620s England – from which they get their name. Head tufts also contribute to the decorative nuptial plumage.

The presence of permanent female mimics in ruffs was discovered and published in a paper in Biology Letters as recently as 2006. These males were called ‘faeders’ by the authors, and they typically make up less than 2% of the population. Faeder males show breeding plumage similar to that of females, and do not have any display feathers. Faeder males aggregate close to displaying males to ‘sneak’ copulations with females and often interfere with copulation attempts by territorial and satellite males. They do face a challenge, however.

Ruffs, like most birds, don’t have an intromittent organ (an external organ of a male, such as a penis, that is specialized to deliver sperm during copulation). Instead, both males and females have a cloaca – the only opening for reproductive exchange, as well as the expulsion of digestive and urinary waste. Sperm is transferred to the female when the male and female bring their cloacas together usually for a few seconds. This means that if a female mimic can get its cloaca in contact with a females, it can transfer sperm, but probably needs a willing participation of the female as well because she has to move her tail feathers aside to expose her cloaca. So there is possibly some collusion involved.

The genetics of the different male phenotypes is reasonably well known. The distinction between territorial and satellite males is controlled at a single gene locus, and follows classical Mendelian inheritance in which the dominant allele produces satellite males, and the territorial (independent) males are homozygous for the recessive alleles.

In 2013 it was reported that there may also be diminutive females, referred to as ‘female faeders’ by their discoverers. Using captive ruffs, in a breeding experiment, the researchers showed that that a dominant allele controls development into male faeders and these small female faeders. These female faders did not produce chicks in the captive flock. This may mean that females pay a cost for having the benefit of faeder males in the population, and this may be a consequence of faeder genetics.

Yvonne Verkuil from the University of Groningen and several colleagues studied associations of faeder males at different scales, and found that faeder males associate with males rather than females, and do so even during the migration. The lekking males leave the breeding grounds first, their job done, and fæders migrate and over-winter with the larger-sized lekking males. This association remains even if it involves the use of suboptimal stopover habitats during migration, and they suggested that any costs associated with the use of suboptimal habitats is compensated by higher reproductive success as sneakers on leks.

The sex ratio in ruffs is strongly female-biased, with males comprising only 34–40 % of the population.

Ruff colour patterns

The breeding plumages of lekking males vary considerably in colour and pattern, this variation is known as polymorphism to biologists. As the breeding season approaches, the independent and satellite males develop ornamental plumage that includes a feather ‘ruff’ and ‘head tufts’, which are individually distinctive in colour and pattern and fixed for the life of the individual. The independents are typically dark-feathered, while the satellite males are typically white-feathered, although this is not a hard and fast distinction.

One of the most prolific ruff researchers, David Lank and his collaborators, have uncovered an interesting aspect of ruff colour variation: what they called visual signals for individual identification. They discovered that breeding male ruffs appear to communicate individual identity through this distinctive, independent variation in colour and pattern of four characteristics their plumages. They suggested that using plumage variation to signal individual identity, rather than voice as used by most other bird species, was favoured by lengthy daytime male display in open habitats in close proximity to receivers. They noted that signalling associated with the peculiar arrangements found in ruff male mating behaviour might also have influenced the evolution of extraordinary plumage diversity. They termed this the “silent song” of ruffs in the title of their 2001 research paper.

Nesting

The female lays one brood of four eggs each year, in a well-hidden ground nest, incubating the eggs and rearing the chicks without input from the males. The nests may be solitary or semi-colonial, sometimes only a few metres apart, and are just a shallow scrape lined with grass, leaves and stems. The chicks are precocial and feed themselves almost immediately on small invertebrates, but are fed by the female as well. As with nesting, males play no part in brooding chicks. Chicks are fledged in 25-28 days, and migrate from the breeding grounds together with the females. Precocial young may be critical in a mating strategy where males play no role in rearing.

The migration

The migration of ruffs begins even before the end of their breeding season in the northern parts of the Palearctic realm, and ends spread out across the Afrotropical realm including South Africa. The migration starts with the departure of the males, who depart well ahead of the females. This makes sense as there is nothing left for them to do at the breeding grounds, given that they do not take part in nesting or the rearing of chicks. Both of the displaying male morphs, which are considerably larger than females, migrate together, and recent evidence shows that the faeder males also mainly migrate together with their displaying counterparts. In some areas, such as eastern Britain and the adjacent western Netherlands, a portion of the ruff population may not migrate at all, instead choosing to stay over the winter.

As noted, ruffs begin arriving in South Africa in August, making them one of the earliest Palearctic migrants to arrive. While they are in South Africa, they are found in most bodies of water around the country, even within arid areas if water is found there. Being waders, the feed mainly in areas with shallow water and mud flats. At Marievale, near Johannesburg, they seem to track water levels, being most abundant when the water is low and lots of wet mud is exposed.

Most have left our area by April, for the long migration back to their Palearctic breeding grounds.

Multi-year mating success

In the mid 1980s, David Lank and Constance Smith showed that the proportion of the total population of males occurring on leks was only12% over the breeding season, but males not using leks also spent about the same amount of time as lek males displaying to females.

Based on ringing studies, it seems that ruffs live up to 11 years (up to 14 years in captivity). This means that aside from genetics, birds can learn over multiple breeding and migration seasons. Both genetics and learning can contribute to the mating success of birds over multiple years.

In the late 1990s, Fredrik Widemo from Uppsala University in Sweden studied ruffs over six breeding seasons, investigating lek stability, site fidelity, male copulatory success, and male dominance relationships. Ninety percent of the territorial males were faithful to the breeding site, both within years and between years. Males that were relatively dominant and successful in their first-year establishment of a territory were more likely to return to the same area, established themselves even earlier in their second year, and had even greater breeding success compared to other males.

The status of the ruff

Ruff breeding populations have declined widely and in all habitats across temperate Eurasia, with the largest populations now restricted to the Arctic tundra. The breeding population has been shifting northwards, leading to the hypothesis that this is a response to global warming. This hypothesis is difficult to test as the situation is also complicated by the fact that, in the more densely populated regions, drainage and agricultural intensification have damaged or destroyed many of the grassland habitats that ruffs use for breeding.

Female choice and the ruff mating system

In his great second book first published in 1871, The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex, Charles Darwin documented a form of selection by mate choice, which became known as sexual selection. In particular, Darwin documented the dominant role of females in mate choice, including among Homo sapiens. Strong female choice can lead to complex ornamentation, bird songs, and mating behaviour.

Sexual selection plays a significant role in the evolution of the ruff mating system, but this is complicated by some features of the ruff system that differ from the classical sexual selection scenario. Classical sexual selection is at its strongest when males are polygynous, mating with more than one female during a single breeding season. In contrast, with ruffs the females are polyandrous, mating with more than one male in a breeding season. Indeed, the level of polyandry in the ruff is the highest known for any lekking species of bird, as well as for any known wader. More than half of female ruffs mate with and have clutches fertilised by more than one male. Females mate with both independent and satellite males more often than expected by chance, and many females include faeder males in their mating.

Since male ruffs do not take part in nesting and rearing chicks, females can choose mates without risking the loss of support from males in these aspects of breeding. Thus polyandry has no significant breeding season cost, but may provide some genetic benefit that could be reinforced by the complex genetics and mate choice that happens in the breeding season.

Ruffs are not just polyandrous, they are also polygynous, and males mate with more than one female as well. This would be expected in a lekking species where males play no part in brooding there would be strong selection pressure for multiple mates, even more so given that a given mating event may or may not produce offspring that they have fathered. The selection effect is simple: males that mate with more than one female are more likely to leave offspring containing the genes that control polygynous mating.

Don Hugie and David Lank (again) published a paper back in 1997 which they talked about “the resident’s dilemma” and discussed a female choice model for the evolution of alternative mating strategies in lekking male ruffs. They observed that resident (territorial male) behavior toward satellites and data on female behaviour suggest that residents benefit from a satellite’s presence due to at least some female preference for mating on co-occupied courts. Thus this is a cooperative association that is favoured by female choice.

Conclusion

So the next time you are out birding and you see some ruffs, spare a thought for the complexities of their lives. They have a lot to teach us humans, both about ourselves, and about the nature of the forces that drive ecology and evolution among the avian dinosaurs that we call birds.