How does the diederik cuckoo ‘know’ what colour egg to lay?

It is summer now, and the “die die diederik” call of the onomatopoeic diederik cuckoo is heard throughout the bushveld. These birds migrate from equatorial regions of Africa in spring, arriving in South Africa starting in October and peaking when the rains come. Their iconic calls herald the onset of summer for many of us. By late April most have finished breeding and left the area to head back to equatorial Africa.

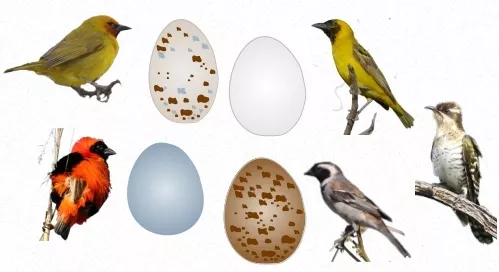

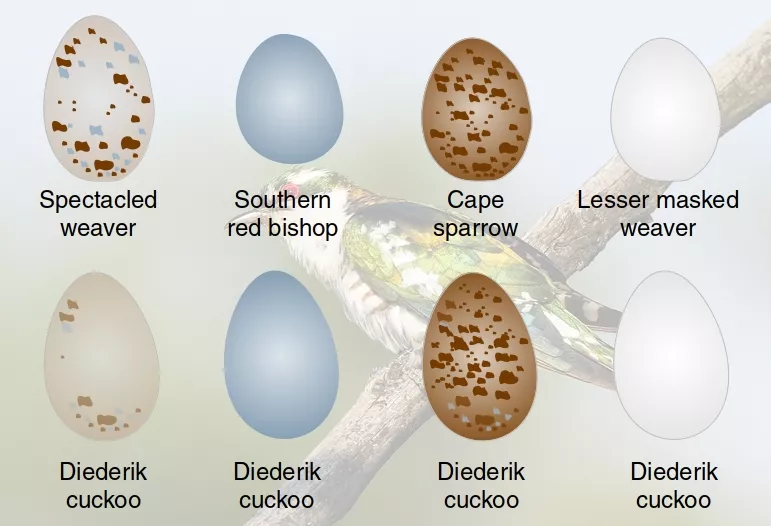

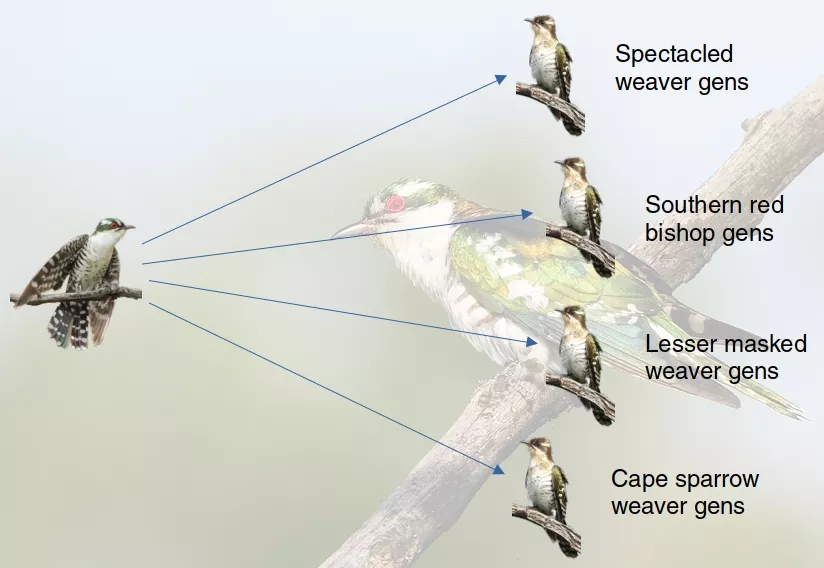

Like many cuckoos, diederik cuckoos are brood parasites, laying their eggs in the nests of more than 24 species of birds. Common hosts include southern red bishop, Cape sparrow, spectacled weaver, lesser masked weaver and southern masked weavers. Strangely, female diederik cuckoos seem to know what colour egg to lay.

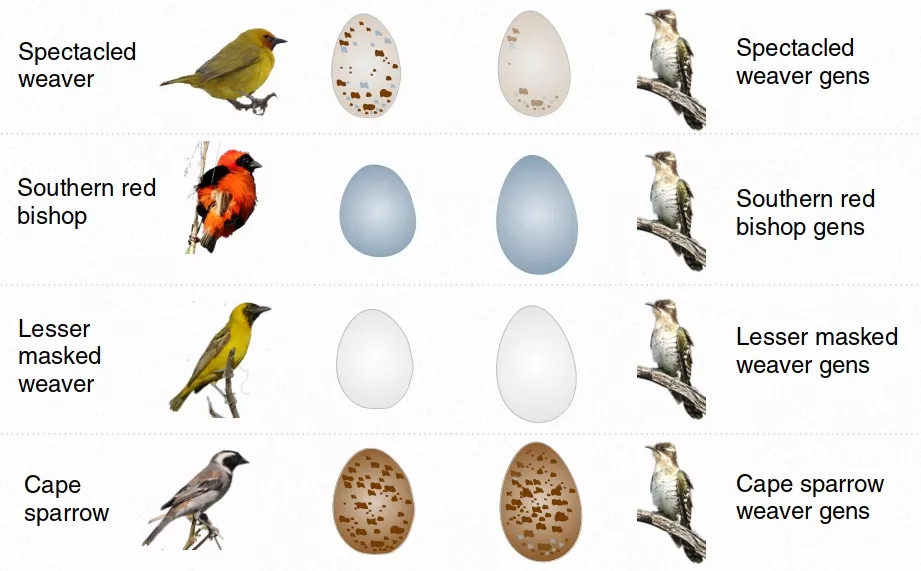

In his Nests and Eggs book, Warwick Tarboton illustrated this for four species, including spectacled weaver, southern red bishop, Cape sparrow and lesser masked weaver. When a female diederik lays an egg in a spectacled weaver nest, it has brown splotches that match fairly closely those of the host. For the southern red bishop, it lays a blue egg like the host, for the Cape sparrow, a splotchy brown egg like the host, and for the lesser masked weaver an white egg.

A common question is “How do the females know what colour egg to lay?” The answer is “They don’t.” Females evolve separate genetic lines that specialise in particular hosts. How this works is a feature of the nature of sex determination and the chromosomes that control it in birds.

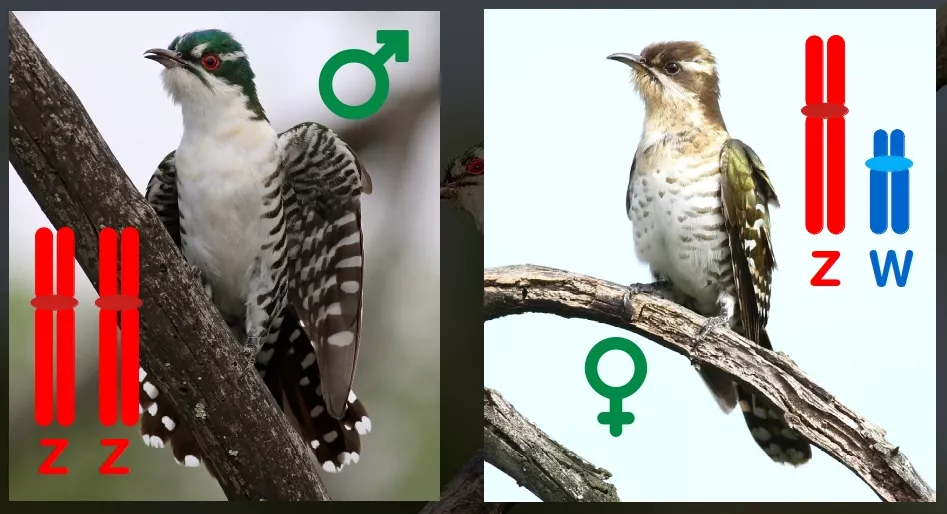

We all know the XY sex-determination system that we humans share with many other mammals and other organisms. For us, females have two of the same kind of sex chromosome (XX), and are called the homogametic sex as a result (homo=same). Males have two different kinds of sex chromosome (XY), and are called the heterogametic sex (hetero=different).

With birds, the females are the heterogametic sex, and we use the letters ZW to denote their sex chromosomes. This means that female birds can carry genetic information on the smaller W chromosome, and this is precisely where the genetic information for host selection is carried.

Any gene on the W chromosome is only passed from mother to daughter. This means that females can produce host-specific lineages, called gentes (singular gens). Each lineage, or gens, is genetically disposed to target a particular host species, and to produce eggs coloured to match the particular host. The genes for a particular specialisation is passed on from mother to daughters via the W chromosome.

Thus, the female diederik cuckoos do not know what colour egg to lay, they have the combination of genetic disposition to lay an egg in a particular host’s nest, and they have the genetic lineage to produce eggs of a particular colour. All of this is determined by old-fashioned natural selection within female lineages.

Natural selection happens just as it would for any other suite of characters, but each gens evolves separately within the species, rather than evolving into a new species over time as you might expect. We could reasonably well ask “Why don’t they become separate species over time?” The answer lies in the males. Since males breed across gens, the integrity of the species is maintained.

And that is the essence of how the diederick cuckoo can lay eggs that match the colour of its host. It is natural selection happening for genes that are carried on the W chromosome of female birds, but held in check because the males never have any of the genes involved.