Oxpeckers and mammals – a relationship only found in Africa

Everyone knows oxpeckers, those strange birds that hang around on mammals and make their living eating parasites, dead skin and blood. Watching them go about their business on mammals such as impala, zebra, giraffe and buffalo can be quite fascinating. There are two species of oxpecker that occur in our area, red-billed oxpecker (Buphagus erythrorynchus), and yellow-billed oxpeckers (Buphagus africanus). Indeed, these are the only two species of oxpecker in the world, and they are only found in sub-Saharan Africa.

Red-billed oxpeckers are much more common than the yellow-billed species in South Africa, although both species have much reduced populations outside conservation areas in part due to the treatment of cattle for ticks. Yellow-billed oxpeckers are only found in the north-east part of the country, mainly in northern Kruger Park, including the broader Hoedspruit area where I live.

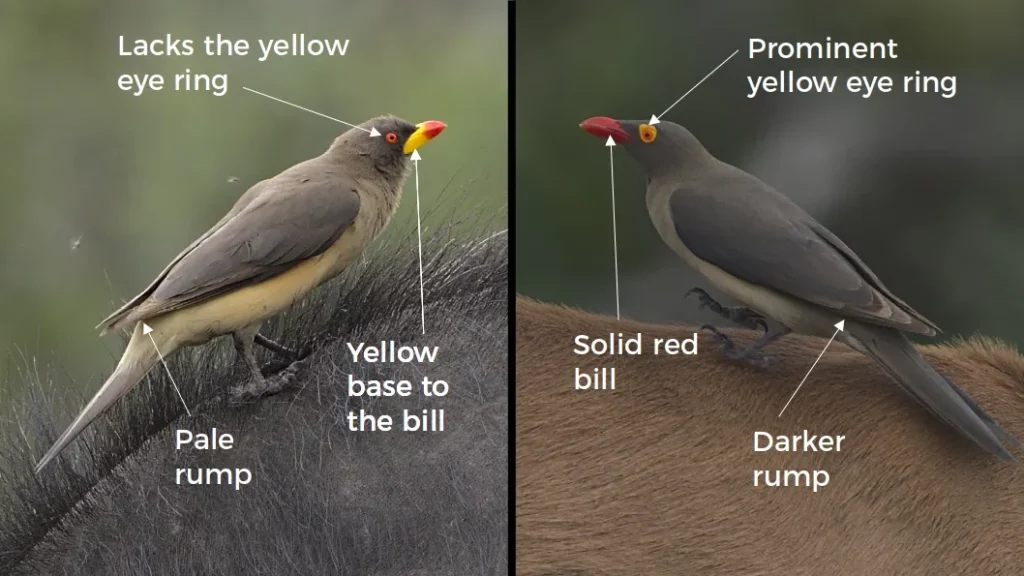

The two species are quite distinct and easy to tell apart under most circumstances. The red-billed oxpecker has a solid red bill, a prominent yellow eye ring that is in stark contrast to the orange-red eye, and a dark rump. The yellow-billed oxpecker has a yellow base to the bill, lacks the yellow eye ring, and has a much paler rump. Male and female oxpeckers within a species are morphologically similar and cannot easily be told apart, at least by humans.

It used to be thought that oxpeckers were members of the starling family, Sturnidae. However, based on molecular evidence they are now placed in the family Buphagidae which contains only these species. The family form a line that branched off before the groups containing the Sturnidae (starlings) and Mimidae (mockingbirds and thrashers), so while related, they are not close to either of these families. This split happened around 23 million years ago.

Oxpeckers carry out their courtship and copulation on their mammalian hosts, something that is easily observed in early summer. Both species of oxpeckers nest in tree-holes that they line with hair plucked from their animal hosts. They are cooperative breeders, with 3-4 adults acting as helpers feeding nestlings and fledglings. The helpers are presumed to be previous offspring of the breeding pair. They typically lay 2-3 eggs, which are incubated for around 12 days, following which the young spend another 28-30 days in the nest before fledging. The fledglings also ride on the mammalian hosts and beg for food from adults feeding on the same host. In good rainy seasons, oxpeckers may nest 2-3 times. Given the loss of trees in the Kruger due to a combination of excessive elephant numbers and perhaps drought, it seems likely that the availability of nest sites for such cavity nesting birds is reduced.

The timing of breeding in red-billed oxpeckers has been studied in Kruger National Park, and found to be strongly dependent on the timing of the rains. This is in turn linked to the increase in abundance of scale ticks (Ixodidae) on the hosts, a food source that is used to help with feather synthesis during the pre-breeding moult. Later, there is an increase in the abundance of horse flies (Tabanidae) and these form a good protein source to enable the oxpeckers to initiate breeding.

Oxpeckers eat a lot of ticks, and in captivity experiments it was shown in the early 1980s that red-billed oxpeckers could reduce adult ticks on cattle by up to 98%. Ticks also accounted for nearly half the food fed to nestlings, with hair and tissues being around 35% for red-billed oxpeckers. Yellow-billed oxpeckers have larger mouths, and are able to feed on the larger, adult ticks, where the red-billed oxpeckers have difficulty.

Oxpeckers use four feeding methods: scissoring, plucking, pecking and insect-catching. Scissoring is used when the bird is feeding on ticks or wounds, and involves rapidly opening-and-closing the bill as it is pushed through the hair or over any part of the the body of its mammalian host. With plucking, sight is important as the body of the host is searched with the head turned sideways, and any visible ticks or loose pieces of skin are seized with the tip of the bill and pulled off with a backward turning movement of the head. Pecking is mainly used for feeding on sores and is a pickaxe-like action with either a slightly opened or a closed bill. Insect-catching involves hawking, random snapping or stalking the insect prey, while remaining on the body of the host.

Both species of oxpecker have evolved a number of morphological adaptations for feeding and life on their mammalian hosts. They have relatively short legs which hold their body clost to the surface, and this goes with robust, strongly curved and sharp claw that allow them to cling in any number of postures while climbing over the mammal’s surface. Stiff tail feathers provide support when they cling to vertical surfaces of their host.

Some studies were done on competition between the oxpecker species where they overlap in northern Kruger National Park. Yellow-billed oxpeckers occur mainly on three hosts: buffalo, zebra and kudu. Buffalo accounted for 56% of sightings, which is also my experience with this species – I see them more often and in higher numbers on buffalo. Red-billed oxpeckers seem to have a much larger number of host species, with impala accounting for the highest percentage at 31%. It seems as though they reduce competition by making use of different hosts.

Tiffany Plantan carried out research for her PhD on the relationship between tick abundance and the nature of the mutualistic relationship between oxpeckers and their hosts. She found that under certain conditions, the oxpecker-host relationship is a nutritional mutualism where the hosts provide food – typically ticks – for oxpeckers in exchange for them rendering a tick cleaning service. Under other conditions, oxpeckers exploit their hosts to feed from their blood and tissue. Not surprisingly, this has to do with the abundance of ticks that the oxpeckers prefer, such that when the host has few ticks of preferred types, the birds would keep wounds open to feed on them to meet their nutritional requirements. Wound feeding is, however, always present particularly in red-billed oxpeckers and is easily observed where there are wounded hosts.

Sometimes biologists study unusual things, and on of the unusual ones was a piece of research by Roan Plotz and Wayne Linklater that showed that oxpeckers help rhinos to evade people. If you have ever tried to get close to oxpeckers you know that they are skittish, often flying away before their host takes any evasive action. Often they issue alarm calls as they fly off, which alerts others nearby and they all take flight. It is not unusual for animals to eavesdrop on the behaviour of other species and use the other animal signals to evade harm, such as the possibility of predation. Black rhino eavesdrop on oxpecker alarm calls and this enabled around 40%–50% of rhinos to evade humans undetected. In the Kiswahili language, oxpeckers are knows as askari wa kifaru, ‘guard or the rhinoceros’ so this has been known for some time!

Learning more

If you want to learn more about birds and birding, join us for a webinar or visit our YouTube channel.