The wood kingfishers: jewels of the bushveld

Visitors from Europe are often surprised when visiting this part of the world when they learn that we have so many species of kingfisher (10 species in South Africa), and that more than half of them are not associated with water. In Europe there is only one species of kingfisher, the common kingfisher, which most people there just refer to as ‘the kingfisher’.

Kingfishers make up the family Alcedinidae, which is divided into three sub-families: Alcedininae (river or pygmy kingfishers), Halcyoninae (tree or wood kingfishers) and Cerylinae (water kingfishers). All three groups are represented in our area, with the wood kingfishers having the most species and being more commonly encountered given our relatively dry conditions with limited standing water away from the large rivers.

Wood kingfishers are very rich in species and genera, with the sub-family containing around 70 species in 12 genera, but all of our representatives belong to a single genus, Halcyon. The famous kookaburras of Australia and Papua New Guinea are wood kingfishers. They comprise four species in the genus Dacelo, including the iconic laughing kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae) of Australia. This group is absent from the Americas, and are thought to have originated in Australasia which still has the most species.

Our species in South Africa include woodland (Halcyon senegalensis), mangrove (Halcyon senegaloides), grey-headed (Halcyon leucocephala), brown hooded (Halcyon albiventris) and striped (Halcyon chelicuti) kingfishers. All except the mangrove kingfisher occur in our area, with this species being a winter visitor to coastal mangrove forests during winter.

With its loud, trilling kri-trrrrrrr call, the woodland kingfisher is an iconic bird of open woodland savannah. It is an intra-African breeding migrant that arrives around October and departs before the end of April. It is easily recognised by its black lower bill and, with its bright blue back, wing panel and tail, few people who have seen it would confuse it with any other kingfisher in our area. It should be pretty common in the Hoedspruit area where I live in the next few weeks.

The woodland kingfisher is widely distributed in tropical Africa south of the Sahara and can be found from the Pretoria area northwards. There are populations that are found both 8° north and south of the equator during the wet season, and they migrate to the equatorial zone during the dry season. There are three sub-species of woodland kingfisher, one of which is apparently not migratory. Their migratory movements are rather poorly known, but some work is being done by researchers at present (you can watch a video about this on the Learn-the-Birds YouTube Channel at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=smQ00U_–jM).

Woodland kingfishers are monogamous, and a pair typically nests in old woodpecker or barbet holes, or in natural tree cavities. They are highly territorial, and they advertise their territory by their distinctive trilling call made from high up or on top of a tree. They often adopt a rather erect posture, and extend their wings quite wide with the trailing wing-edge pointing downwards. This allows them to display their white under-wing coverts and contrasting black flight feathers, presumably as part of their territorial display.

Grey-headed kingfishers are unmistakeable, and are probably my favourite species in terms of colour and striking pattern. It is a kingfisher of dry scrub and woodland, and is often found near water despite the fact that it is not aquatic. I have watched them feeding in Kruger National Park. They typically perch on a branch, often hidden from direct view, without moving while watching the ground for signs of prey. Their prey includes insects and small lizards. They may bob their head excitedly before diving on a prey item, and then return to the same or a nearby branch.

They have a very prominent grey head, and a red bill. The back and upper wings are black, and it has a chestnut coloured belly with blue outer wings and tail feathers. I find the outer wing and tail colours to be so dark that they often look purple to me, which I find quite distinctive in all the individuals that I have seen. It is not very common in our area, but becomes more common further north, especially around Punda Maria in Kruger and in Mapungubwe.

The sexes are similar to the human eye, although the male is said to have duller chestnut underparts. The species nests in holes in steep riverbanks rather than trees, and it protects its nest aggressively by repeated dive-bombing monitor lizards and other threats. Grey-headed kingfishers are parasitised by greater honeyguides (Indicator indicator).

Brown hooded kingfishers are pretty much ubiquitous throughout eastern half and southern part of South Africa. They are very common in the Hoedspruit area, and are particularly common in the trees along our seasonally dry rivers. There are at least two of them that are in the trees in front of my house almost every day at present. There is partly fallen tree that is bent horizontally at about the height of my chest, and one of them is almost always sitting there in the morning looking for insects in the open canopy. Last Sunday one of them caught a large scorpion, and sat on another branch bashing it over an over in typical kingfisher fashion.

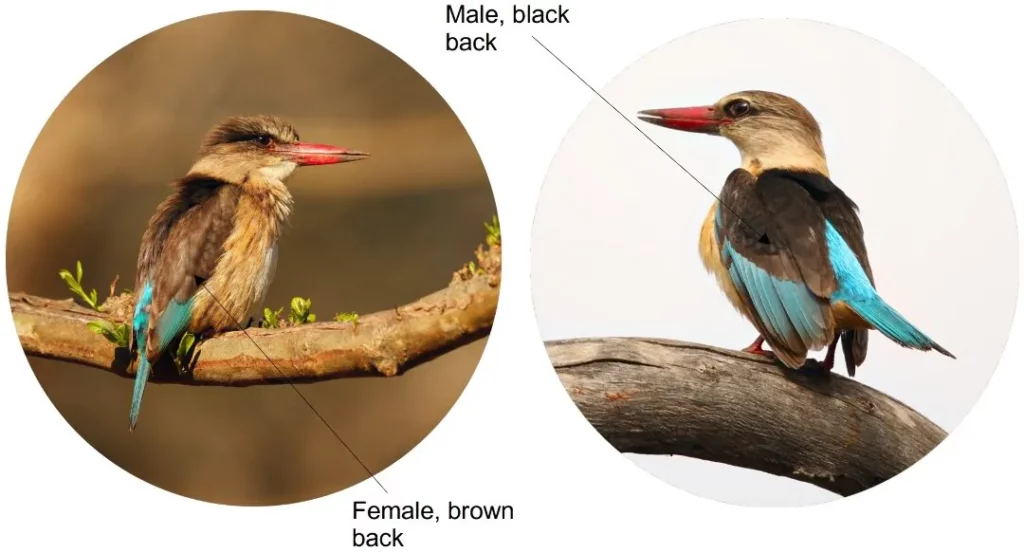

Unlike the other species mentioned here, brown-hooded kingfishers have distinctive sexes. They are not radically different, but it is easy enough to tell them apart, for the males have a back back and wing coverts, while females have medium to dark brown backs and wing coverts with underparts that are more streaked than the male. Like the grey-headed kingfisher, this species also excavates a horizontal tunnel in vertical river banks, and lays eggs on the soil about a metre back from the hole.

Striped kingfishers can be easily confused with brown-hooded kingfishers, but they look mostly greyish brown on the upper part of the body when perched. The blue of the lower back and outer flight feathers are better seen when they flash as it is in flight or displaying from a perch. A white patch at the base of the primary flight feathers is usually visible even when it is perched, but is very prominent when it is displaying or its wings are open in flight.

Striped kingfishers are very territorial, and is known to chase off other kingfishers, shrikes, doves, rollers and I have even been dive bombed by one. They have quite a large territory, up to three hectares in size with as many as 100 tall trees. At a site in Gauteng, I walked around the territory of a pair, and they stayed with me most of the time, keeping an eye on what I was doing. The territory owner will call from early morning up until mid day, after which it typically goes quiet and can be very difficult to locate. If you want to find one, the best time is before 10 AM, just listen for its calls, and head towards them.

Recent genetic analysis indicates that the tree kingfishers together with water kingfishers branched off from their most recent common ancestor with all other kingfishers back in the late Eocene epoch, approximately 37-35 million years ago. Tree and water kingfishers thus last shared a common ancestor at this time, so this sub-family has been around for over 35 million years, and underwent adaptive radiation throughout the Miocene epoch, from at least 20 million years ago. A lot was happening with birds at this time, and the climate was cooling and getting drier, with grasslands replacing forests and lots of species going extinct. Unfortunately, the fossil record of birds from this time is poor, and relatively little is known about their Miocene evolution except from genetic data.

4 Responses

Kingfishers are absolutely lovely! So interesting to learn about wood kingfishers. I’ve seen many Belted Kingfishers here in the U.S. and hope to see more wood kingfishers someday.