Swifts and Swallows: Convergent Evolution in Action

I live in the Hoedspruit area of Limpopo province of South Africa, and every summer, our skies are full of agile and fast birds flying around picking insects out of the air. In the dying days of our summer, some such as the barn swallow, muster in large numbers in trees and along wires for the long journey back to the far reaches of the Northern Hemisphere. Given that swifts and swallows are so similar in form, habits, and feeding, one could be forgiven for thinking that they are related. They are not!

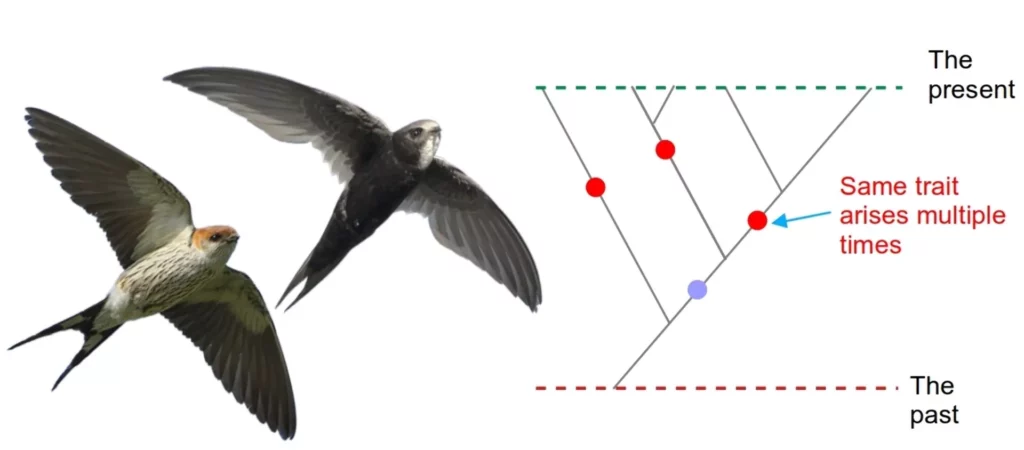

They resemble one another because of a process known as convergent evolution. This is the evolutionary process whereby organisms that are not closely related independently evolve similar traits as a result of adapting to similar environments or ecological niches.

A niche is basically the total way of life of a species. Another way to look at it is to consider the match of a species to a specific set of environmental conditions. This may include aspects such as food and feeding, behaviour, reproduction, predators and avoiding predation, competitors and competition, as well as parasitism and the challenge of parasites. The more the niches of two species overlap, the more intensely they compete, and this can create selective pressure for differentiation.

The other side of this coin is that as two species or groups of species begin to occupy similar niches, the more closely they come to resemble one another in form and function. Let’s look at this from the perspective of a food resource that is available – flying insects. Any group of birds that can evolve to hunt insects on the wing will gain some competitive advantage over more sedentary feeders, and reduce the niche overlap with them, thus reducing competition.

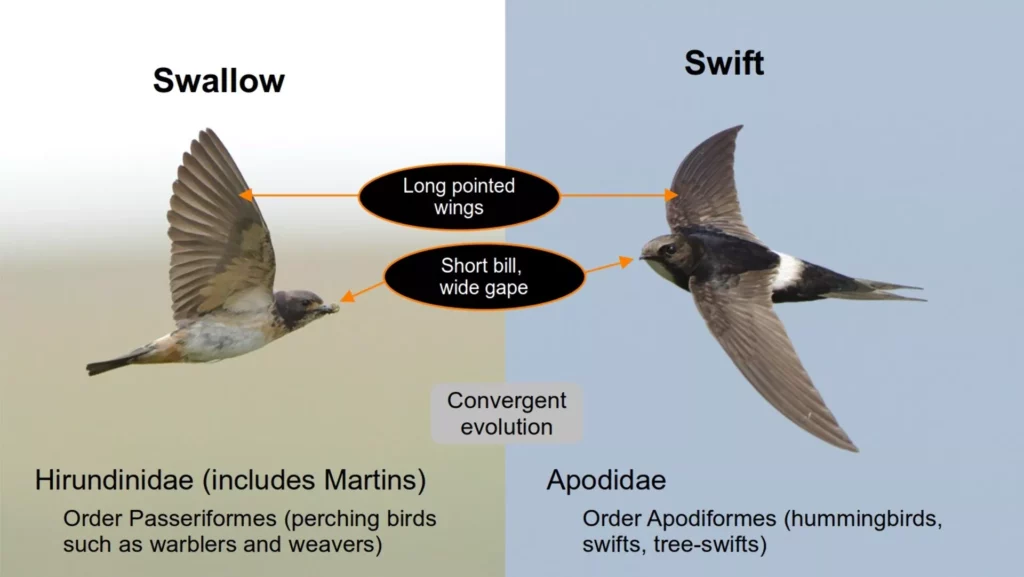

The swallows (family Hirundinidae, including martins and saw-wings) and swifts (family Apodidae) represent two completely different groups of birds that adapted to hunting insects on the wing. They don’t just belong to different families of birds, they belong to two completely different orders. Swallows belong to the order Passeriformes, the perching birds such as warblers and weavers. Swifts are closer to hummingbirds and are placed in the order Apodiformes (although Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy raises this group to a superorder, the Apodimorphae). The Apodiformes evolved in the Northern Hemisphere, probably during the Late Paleocene or Early Eocene, so swallows and swifts have not had a common ancestor for many many millions of years.

Both groups are adapted to hunting insects on the wing and have developed a slender, streamlined body and long, pointed wings, which allow great manoeuvrability and long periods in the air that include frequent periods of gliding. They also have they have short bills, strong jaws and a wide gape, characteristics that they also share with night jars.

Swallows and relatives in the Hoedspruit area include barn swallow, lesser striped swallow, mosque swallow, red-breasted swallow, wire-tailed swallow, brown-throated martin, common house martin, sand martin and black saw-wing. Swifts in our area include the African black swift, African palm swift, alpine swift (most commonly seen up on the panorama route, along the edges of cliffs), horus swift, little swift (the most common one around Hoedspruit), and white-rumped swift.

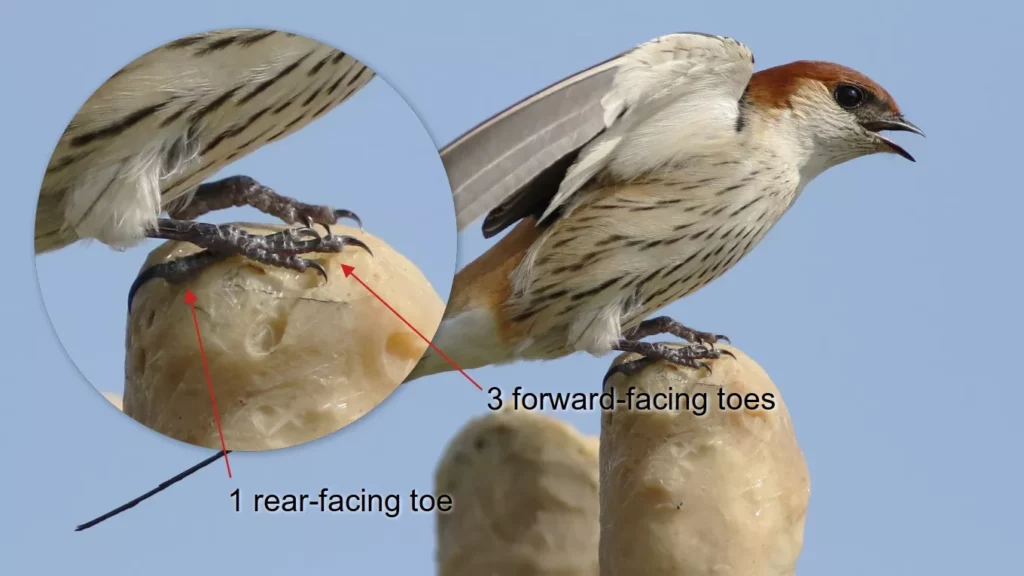

Convergent evolution can create confusion in how we understand relationships among organisms because the same trait evolves multiple times in lineages that are not recently related. Fortunately, birds often provide clues that can lead us in the right direction, and the most obvious one with swallows and swifts is in the feet. As passerines, each foot has three toes directed forward and one toe directed backward, and this helps them perch upright on tree branches. Swallows and their relatives often perch in trees, and if you ever watch barn swallows feeding you will know that they often spend time in trees between feeding bouts.

The feet of swifts and other Apodiformes are different. Swifts have short legs and very small feet that are equipped with sharp, curved claws adapted for gripping onto sheer cave walls and cliffs. Swifts cannot perch on trees, and you pretty much never see them doing so. These differences tell us that despite their similarities, these birds are not closely related. Nowadays, this is also confirmed by DNA evidence.

So the next time you are out and you see birds flying around catching insects, see if you can tell if they are swallows or swifts. If you watch them for a while, you will soon see the differences!