A family of specialised nest parasites

Most people are familiar with the nest parasitism – or brood parasitism – that is shown by our cuckoos, such as the Jacobin cuckoo and Diederik Cuckoos, where the birds lay their eggs in the nests of other bird species. These other species, the hosts, then feed and rear the young as if they were their own offspring. There are two other groups of birds in our area that are also brood-parasites, the family Viduidae (indigobirds, whydahs, and cuckoo-finch) and the family Indicatoridae (honeyguides). In this article we will focus on the Viduidae, a family that is well represented in the Hoedspruit area including three species each of indigobirds and whydahs.

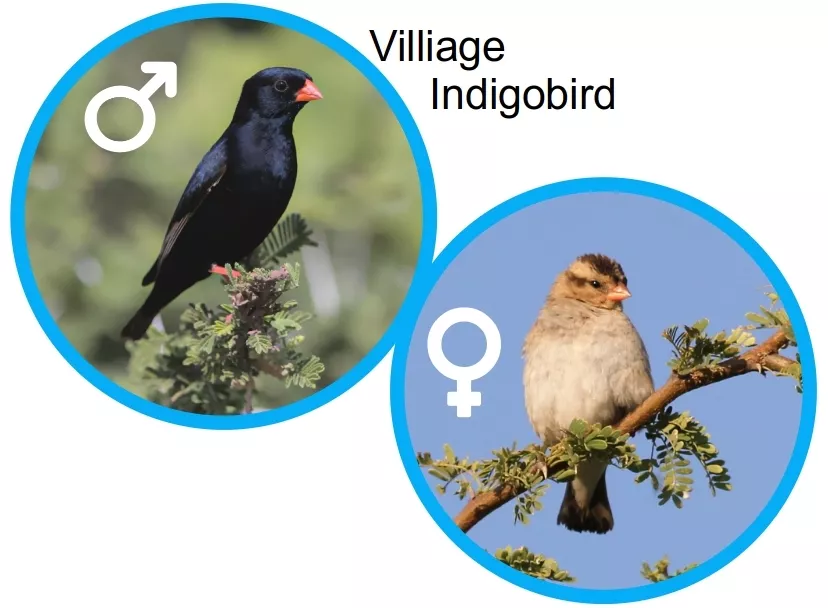

The Viduidae comprises small, finch-like perching birds birds that are native to Africa. All species in this family are dimorphic, which means that there are significant differences between males and females. In the indigobirds, males have predominantly black or indigo colours in their plumage, while in whydahs breeding males have have long and sometimes ornate tails. In the cuckofinch, males are bright yellow with a black bill in the breeding season. Females of all species are brownish, do not have long tails, are much better camouflaged than the breeding males. Males lose their breeding plumage outside the breeding season, and become much more like females in appearance.

With the exception of the cuckofinch, all Viduidae belong to the genus Vidua irrespective of whether they are indigobirds or whydahs. Here we are only going to be looking at this genus, ignoring the cuckofinch for now.

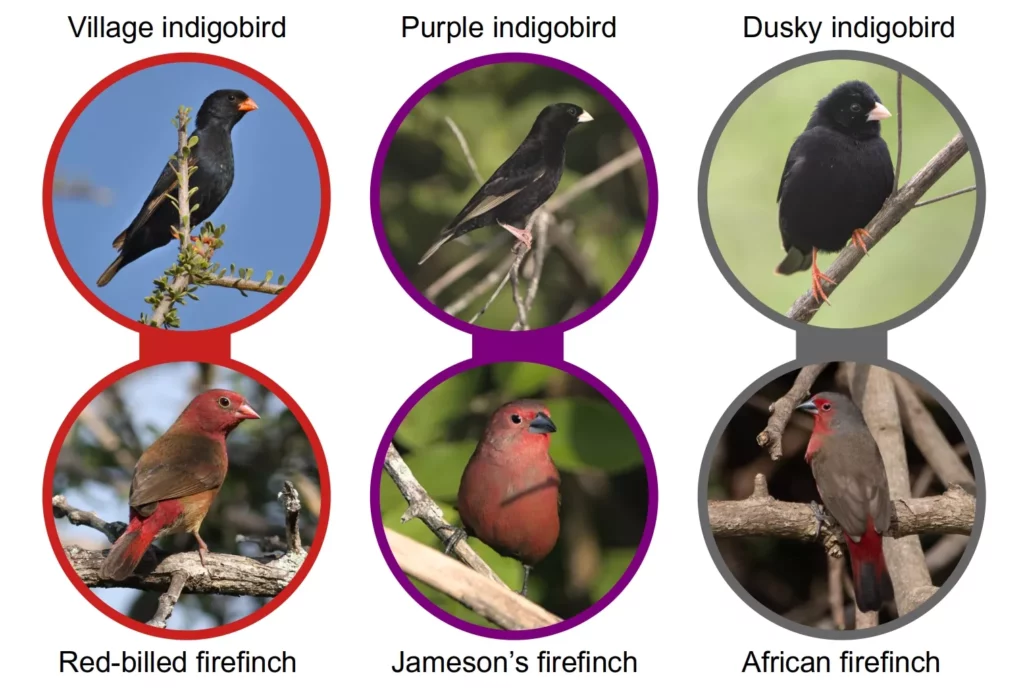

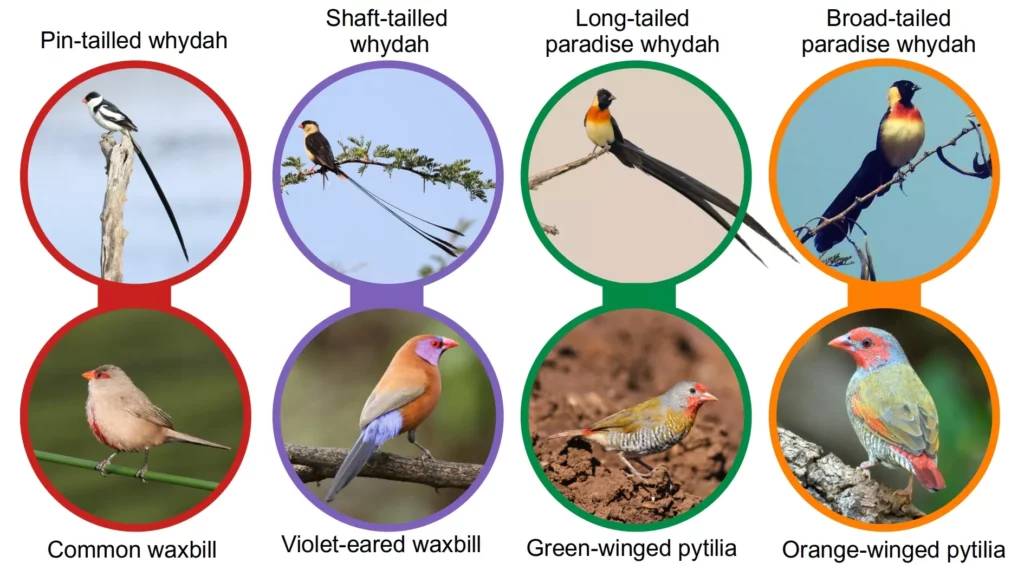

Each species of indigobird and whydah is an obligate brood-parasite, primarily laying its eggs in the nests of estrildid finch species. Estrildids – which are not closely related to actual finches – comprise a family (the Estrildidae) of small seed-eating passerines of the Old World tropics and Australasia. Members of this family are commonly known as crimsonwings, firefinches, mannikins, munias, parrotfinches, pytilias, twinspots and waxbills. The estrildid family is well represented in Africa and contains some of our most colourful small birds.

Vidua species are highly specialised when it comes to their hosts. Indigobirds typically use firefinches as hosts, with each indigobird species limited to a single species of firefinch, although with some geographical variation. In our area, the village indigobird parasitises red-billed firefinches, the purple indigobird parasitises Jameson’s firefinch and the dusky indigobird parasitises the African firefinch.

Some of the whydahs may be a little more flexible in their hosts, with the pin-tailed whydah known to have at least 10 host species, with different species predominating in different parts of its range. Its main host in our area is the likely to be the common waxbill. On the other hand, both the long-tailed and broad-tailed paradise whydahs are highly specialised to different species of pytilia (previously melba finches).

In other brood parasites, such as cuckoos and honeyguides, the parasites often destroy one or more host eggs or young, but indigobirds and whydahs don’t do this. Instead they lay 1–4 eggs in the host nest, adding to the host eggs that are already there. Their nestlings may, however, have some tricks to help them score a larger share of the feeding by the host parents.

Given their high level specialisation, Vidua species have evolved a number of specialised adaptations in which they mimic their hosts. Vidua species typically imitate the song of their host, which the males learn in the nest. Females of the same species learn to recognise the song of the host sung by the male of her species, and is thus able to choose males with the same song as the host in whose nest she will lay her eggs.

Imitation of the host does not stop there, for the nestlings mimic both the mouth morphology, begging calls and behaviour of the host. The mouths of estrildid nestlings often contain spots and other markings that line the gape and palate. These are are peculiar to a particular species, and that are signal to illicit feeding responses by the parents, ensuring that the parents feed their offspring on a regular basis.

Dr Gabriel Jamie and colleagues studied mouth markings in viduid parasites and their estrildid hosts, and found that the nestlings of the viduids evolved features to mimic the colours, patterns, sounds and movements of the nestlings of their particular host species. Gabriel’s work makes fascinating reading, and fortunately he has also written some excellent ‘popular articles’ on his work (see under ‘Further reading’).

This mimicry is illustrated for one of the parasite-host combinations common in our area: purple indigobird and Jameson’s firefinch. Birds do not see colours the same way we do, so in his work Gabriel processed the images of the nestling palates (middle images below) through a model of bird vision so that they could be viewed as the host parent would see them (right images below). The markings on the palate are almost identical between parasite nestling and host nestling. Showing these markings to the parent is considered to be begging signals that prompt the parent to recognise the nestling and provide food.

The same concurrence of host and parasite nestling mouth markings were present in other host-parasite pairs, but it is not just the mouth markings that are mimicked. The begging calls were also mimicked by the parasite nestlings, further contributing to ensuring that the host parent feeds the parasitic nestling.

There are other lessons in evolutionary biology in studying this group, but they are beyond the scope of this article. You may wish to download Gabriel’s African Birdlife article, which goes into a lot more detail. Hopefully, when you next see these birds, whether viduids or estrildids, you now have a better understanding of the relationships between them, and the strange evolutionary outcomes within this host-parasite systems among these common birds in the Hoedspruit area.

FURTHER READING

Gabriel A. Jamie. 2021. Big Little Liars: Parasitism, mimicry and speciation in the indigobirds and whydahs of Africa. African Birdlife, January/February, pp 34-41. Download from http://www.fitzpatrick.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/275/Publications/semi-popular/2021/AB09%282%2934-41.pdf

CREDITS

Male African Firefinch image by Sithembiso Blessing Majoka, used with permission.

Research images of palate of purple indigobird and Jameson’s firefinch nestlings, as well as Jamieson’s firefinch nestling gape by Dr Gabriel Jamie, used with permission.

Broad-tailed paradise whydah and orange-winged pytilia by Derek Adams, used with permission.